September

I am haunted.

By memories that flash like ghosts across the back wall of my mind. Haunted by battles I’ve fought with myself. September now and I am back in Colorado. Working at CSU-Pueblo again I’m reminded of my first teaching job when, seven years ago this month, I left the U.S. for the Middle East after accepting a position at the American University of Beirut. I’d grown up during the Lebanese Civil War and, like background noise, it was always around. News of bombings in Beirut. Reports of the death count rising.

But I never paid attention.

I had no idea I’d ever try to find Beirut on a map. Let alone live, work, and lose my mind in that wild corner of the Middle East. Of course the massacre of innocent people bothered me. Wherever it was rumored. But the word Lebanon had always been an abstraction at best. A name I associated with great distance, a vague sense of danger, its conflicts unfolding on the other side of the world over issues that had nothing to do with me.

During my four years studying in Ohio, I’d dreamt of returning to Alaska. Or some place like it. Instead, at the end of it all, I found myself aimed in the other direction. Across the Atlantic. And Mediterranean. Toward a new kind of wilderness, cloaked in exotic fragrance and smoke. Grime. Beirut’s labyrinth of concrete, rebar, and rubble. Mysterious customs and tongues.

After graduating from Ohio University, during a deepening recession, I applied to over sixty jobs—none of which were in Alaska unfortunately—and was lucky that not only one, but two schools offered me positions. Northwestern College, a small Christian school in Orange City, Iowa. And the American University of Beirut.

Even if I was raised Lutheran, Northwestern was not a great fit, though it could’ve been a stepping stone to something better. And, compared to Beirut, I would’ve known exactly what to expect. A small town on the prairie laid out in a simple grid connecting manicured lawns, modest houses, and small conservative churches. A wholesome, mostly white student body required to attend Chapel three times a day.

If there had been no other option, I would’ve taken it—grateful for a paying job in my new field—and tried to make the most of it.

But, instead there was Beirut.

Which, like the Alaska dream of my childhood, represented all the excitement, enigma, and danger of the unknown. The mystery of the Orient was also the power of her seduction. Those hypnotic, Byzantine rhythms playing out in my mind’s imagined melodies. Even if, instead of Iowa, I’d had another job offer in Montana or Colorado, it would’ve been hard to turn down Lebanon. The larger, insane part of me, drawn to chaos and turmoil, would’ve always wondered. On the other hand, even if all Hell broke loose in Beirut and I hated it from the first day, that same crazed side would never have to wonder what it would’ve been like. Either way, I didn’t think I’d ever regret moving to the Middle East. And unlike Orange City, I knew that in Beirut, despite the risk, or maybe because of it, I would never be bored.

So I accepted AUB’s offer, spent that summer securing a work visa and all the necessary shots. By the end of it I’d been vaccinated against nearly every threat to the immune system. Cholera, Hepatitis, Malaria. Egyptian Eggs.

Even the plague.

On September 23, 2009 I got on a plane. Forty-two hours later, after a transatlantic flight to Germany, six hours of shuteye on the floor of the Frankfurt airport, and a choppy five-hour jump to Lebanon, I landed in Beirut.

I’d vowed to return to Alaska after finishing in Ohio, no matter what. At the time, I could never have imagined a place like Lebanon ever coming into the equation. Or the intense desire to use the degree I’d just earned. But there are no excuses. I changed my mind, would have to deal with the consequences. And by getting on that plane, I’d crossed my Rubicon. For the rest of my life, I’d never be the same. Which is probably why I didn’t think much more about it until the plane taxied down the runway, gathered speed, and lifted off the ground.

A sliver of light outlined the horizon. What looked like distant mountains dropping into the sea. Dawn spread out, and I could see beyond the high rises to the Mediterranean, where it met the rugged coast of Lebanon. I’d tossed and turned half the night, finally given up, and spent the predawn hours staring into darkness outside the hotel window. I could see the forms of skyscrapers all around, but it was too dark to pick out details.

My plane had landed just before midnight. A cab driver, already waiting on the street outside, didn’t speak English but held up a sign: ARNEGARD.

The drive from the airport to the Gefinor Hotel, where AUB was paying for me to stay until they helped me find an apartment, took about half an hour. It’s hard to say though. Jet-lagged and disoriented, I recall it mostly as a blur. But from what I could see I remember grey apartment buildings stacked on top of each other. Occasional high rises constructed from what, even at a distance, looked like the cheapest concrete and plaster. One building had been bombed out. No glass left in the windows. No roof. Rebar twisting out of the tops of the walls.

We passed an empty lot full of palm trees. Then another a few blocks later. This time filled with trash and debris. No trees or vegetation whatsoever. Chain link fences with whole sections trampled. Cement walls, topped with razor wire, but blown in half or crumbling in various stages of ruin.

The only color in the city came from its graffiti. The squiggly, rounded symbols of Arabic letters. A yellow flag with a hand holding a machine gun. A billboard image of a bearded man in a long black robe. An important leader from the looks of him, but his shoulder was torn and flapping in the breeze.

We passed a concrete high rise missing its front wall, floors and staircases intact inside, like the cross section of a model skyscraper. Old blankets hung between many of the buildings’ cement balconies. Somewhere along the way we stopped at a checkpoint. The cab driver exchanged words with a young, Arab guard carrying an AK-47, and the gunner waved us on. Past concertina wire, orange blockades, and two tanks facing us on either side of the road.

That was around midnight. And after two days of flying, it felt more like a dream than anything else. But as I woke the next morning, opened the blinds of my hotel window, and watched the sun rise above Beirut, reality began to take hold.

* * *

The Housing Department secretary picked up the phone on her desk and told Antoine I was there. She hung up and let me into a room across the lobby.

On the far side of a huge, plush office, a man swiveled around in a chair, stood, and offered his hand as he approached. He towered well over six feet with a white widow’s peak slicked straight back.

“Antoine Chahine,” he said as I shook his hand. “They told me you’d be coming. Have a seat.” He gestured toward a leather chair. “So, you need a place to live.” Antoine looked out his window absently. “There’s really not much right now. Because of Francophone, the entire city’s overbooked.” He explained that Francophone was a huge soccer tournament and festival, and Beirut was this years’ host. “There’s really only a couple available apartments in the whole city. I can put you in one of those for a month until the tourists leave, then we can find another place for you.”

I shrugged and said okay, not realizing at the time that he had no intention of ever finding me another place to live.

“Ghassan will show you the apartments, and you can choose one.” He picked up his phone and spoke Arabic to someone on the other end.

“It was nice to meet you.” Antoine opened his door for me, and when I walked back out, a short, older man stood by the secretary’s desk.

“I Ghassan,” the man said. “Come.”

We walked around the building to a small parking lot and a rusted out International pickup. Samer opened the driver’s door and nodded for me to get in the passenger’s side.

He showed me only two apartments that day. The first, a rundown, grey building tucked away in an alley lacking direct light. The second, a more modern apartment complex called the Orient Queen. Both 1,200 bucks a month, 800 after the subsidy.

I chose the Orient Queen because it was near campus and from my new balcony, if I craned my neck, I’d be able to see a sliver of the Mediterranean between two crumbling high rises. But the Queen was nothing special. It would be like living in a hotel room with a tiny kitchen attached. Otherwise just a bed and bath. Still, it was more than enough for me. All of my belongings had fit in a duffel bag and backpack.

Hamra شارع الحمراء

It hadn’t stopped pouring for a week. Angled by wind, the fat drops fell sideways. Horizontal at times. Rainwater, axle deep, rushed down the streets of Hamra—my neighborhood—flushing debris out toward the Mediterranean. Friday night, and I was late meeting my new friend, Zahra—a mystic from the Chouf. Despite the umbrella I bought from a street peddler, I was soaked by the time I showed up at the small, dimly lit restaurant we’d agreed on.

Zahra was already seated when I ducked through the door and the waiter walked me to the far corner where she’d saved us a table.

As I approached, she stood and I kissed her on the cheek. Keefik? I asked. How are you?

“Good,” she said. “You?”

“Wet.”

We sat back down and the waiter poured our waters, handed us both menus. I’d decided to try the raw meat that night. A month ago I’d had my first Fatouche and Tabouleh here. At the time my stomach was still reeling from some local produce, but I’d gotten used to the food and water, and tonight I was trying Kafta: Uncooked lamb, ground with onions and spices.

After we ordered I asked Zahra about work, and she said it was fine, she just missed the mountains. And her home—Ramleer.

“I’m a village girl,” she said with a smile. “Beirut is too much for me.”

I nodded. “I know what you mean.” I’d told Zahra that before moving I was working on a family farm for the summer. Near the badlands of North Dakota. In a county as big as Lebanon with only five thousand residents.

“It’s too big for me, too,” I said.

When the waiter brought our food, Zahra glanced at the Kafta on my plate. “That’ll bring out the Druze warrior in you,” she said.

Zahra grew up in a mountainous region of Lebanon guarded by her people for almost a thousand years. Long before fleeing persecution in Egypt the Druze splintered away from Islam to write the Book of Wisdom, a mystical interpretation of the Koran, though Druze reflects elements of Christianity, Judaism, even Buddhism. Their religion had never been institutionalized. Initiates retreated to solitude, studied the Book of Wisdom, and returned to instruct others. But were only teachers. Spiritual interpreters. All Druze prayed directly to God.

“Though most are peace-loving,” Zahra said, “Druze become the fiercest warriors when attacked.” Despite her hatred of violence, pride rose in her voice as she reminded me that no enemy had ever taken the Chouf. No Byzantine or Crusader. Even during the Civil War the Israelis never occupied her people’s land. And the Druze were the only Lebanese to ever defeat Hezbollah in battle.

During the May War of 2008 countless Druze ex-pats left high paying jobs around the world, flew back to Lebanon and defended their homeland. From England, India, the United States, Druze men traded their business suits and brief cases for fatigues and machine guns and protected the Chouf from vicious afronts on all sides.

Zahra was a believer in possibilities and, despite the brutality she’d witnessed, saw hope and virtue in nearly all people. Working for the United Nations downtown, she drafted peace negotiations and helped enact the treaty of 2006 that ended the July War with Israel. She was the best at what she did and loved her job. It’s what kept her and her mother, Nadwa, in Beirut instead of at home in the mountains.

I wondered if the same pacifist nature is what made the Druze the outlaw minority of the Arab World. They didn’t attack or convert. The only way to become Druze was to be born Druze and as a consequence their numbers had never really grown. Only five percent of Lebanon’s population, Zahra’s people had always had less political power. And I knew it bothered her. So I wasn’t surprised when she suddenly changed the subject.

“How’s the Kafta?” she asked.

“Really good.” And it was true. Even cold, it was some of the best meat I’d ever had.

I still wanted to ask her more about the Druze. How they’d spared their homeland from so many enemies. But I could tell Zahra was done for now. She dealt with enough war at work.

When we finished dinner we walked out through the front door, surprised to see the downpour had diminished to a sprinkle. It was only a few blocks to the Daouk Building where Zahra and her mom lived in a third floor apartment. As we approached, Nadwa waved from a cracked concrete balcony, pockmarked with bullet holes.

“Up in a minute,” Zahra hollered.

I gave Zahra a hug and thanked her for meeting me.

“Sure,” she said. “Let’s do it again soon.”

I smiled. “I’d like that.”

On the walk back to my apartment, wet streets and sidewalks glistened. Storefronts were quiet and, up above, bedroom windows darkened one by one. Beyond the rooftops, clouds dissolved in the blueish glow of a waxing moon.

On The Job في مكان

At AUB I had Shi’ite and Sunni students. Druze, Palestinian, Greek Orthodox, Maronite, and Atheist. A few wore traditional burqas, hijabs, or head scarves, but most dressed like average American college students. They wrote powerful and poetic essays. Even though English was no one’s first language, they’d mastered it and used it to tell the most descriptive, beautiful stories.

Christian wrote about his Armenian ancestors, how they narrowly escaped genocide by the Ottoman Empire, and walked across the desert for four days without food. Hiding in caves and drinking from mud puddles until they reached Lebanon.

Mohammed wrote a story about his sister who had dreamt of becoming a dancer until the Summer War of 2006 when an Israeli bullet paralyzed her for life. Now, when she asked Mohammed to take her dancing, he’d carry her up to their apartment’s rooftop, where he’d built a makeshift swing, and push her back and forth in the hazy air of downtown Beirut.

Lebanon was so splintered that my students had never studied history after World War II. Public schools didn’t teach it because no one could agree on such a complicated past. Whoever wrote the textbook—the Arab Christians, Sunni or Shi’ite Muslims, the Palestinians or the Druze—would each have their own unique stories to tell. No one could agree on who started the Civil War. The Maronite crusader who shot a busload of Palestinians the day the country erupted in tumult? Or the Palestinians who set up their base of operations in Beirut to wage war against Israel? Was it the fault of Israel for displacing millions of innocent people to begin with? Were the Christian terrorists to blame? Or the fundamentalist Muslims?

Things get a little confusing when Western countries, like France and England, start divvying up foreign lands. Where rivers and mountains once separated opposing tribes and cultures before World War I, suddenly arbitrary, geometric lines brought fierce enemies under the same laws. Clans who wanted nothing to do with each other found themselves sharing the same flag.

Lebanon was permanently scarred. Too many conflicts to count—the Civil War often called the Big War so as not to confuse it with all the smaller wars before it. Or since.

And it was even more confusing to me.

Luckily, I had my students to teach me about Lebanon’s history and politics. Samer, an awkward, lanky kid, always wanted to talk, and after class we’d walk across campus together.

“So, why did you come here?” he once asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I just wanted to see Beirut. To learn more about it.”

He stopped and turned. “You just wanted to see Beirut? You mean, you didn’t have to come?”

“No. I had another job offer, but I wanted to experience the Middle East. To see for myself what it was really like.”

We started walking again and Samer shook his head. “I just want to get my degree and find a job in the States. I don’t want to witness any more violence.”

Samer had told me about the summer war of 2006. How he’d seen the battleships cruising the Mediterranean from his bedroom window. Felt bombs rattle the walls of the small apartment he and his father shared.

Finally reaching his bus stop on the other side of campus, we’d stop.

“Mooshrant,” I’d tell him. Goodnight.

He’d always smirk at my pronunciation. Then say, “I’ll see you tomorrow, Sir. Goodnight.”

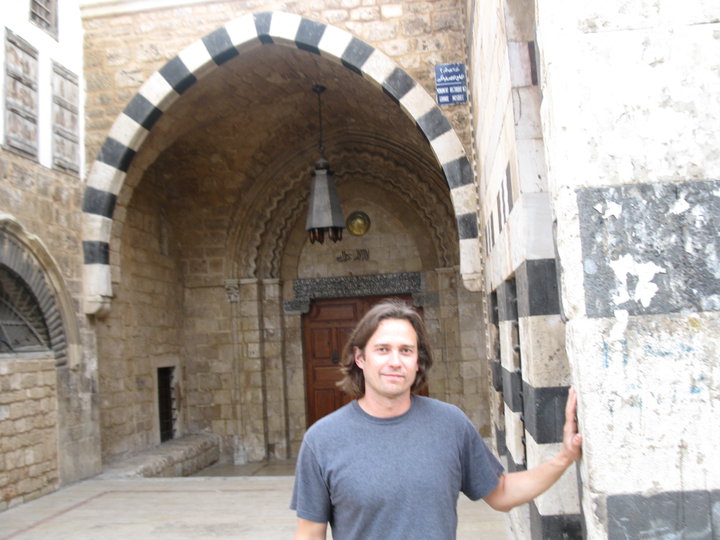

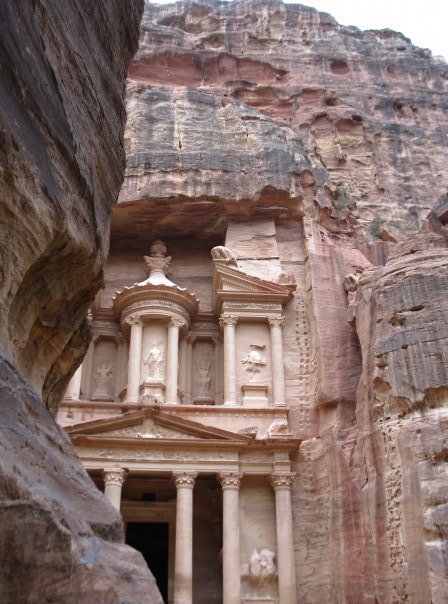

From Beirut I was able to travel to the most amazing parts of the Middle East. The Dead Sea. Mt Nebo. Petra. The baptismal site of Christ. Damascus. Even the pyramids.

But it was the other parts of Lebanon that were the most interesting. Once you drove north, out of Beirut, the country was pristine. Breath-taking. Most of the people in the rural areas would give you the shirt of their backs. Qadisha. The Sacred Valley. The ruins of Baalbek. And the towering cedar groves in the mountains up north. All some of the most beautiful places I’d ever seen.

Still, my time in Beirut, wasn’t all fun.

Car bombings and the constant threat of war took their toll. I missed the U.S. much more than I thought I would. Missed other Americans. And all the freedom I’d taken for granted in the States. I especially missed the American West. The Rockies. The wilderness.

So, I was incredibly lucky when I landed my job in Colorado. Although a lot went wrong before I made it home.

I met a Lebanese woman. Our courtship was fast and furious and we were married way too soon. It was my fault. I’d not understood the social codes of the Middle East. How fast it can happen. How people don’t date in Lebanon the way we think of dating in the U.S. How, if you visit a woman’s village, her community, friends, and family, you’d better already be engaged. They’ll be expecting it. She’ll be expecting it.

And soon.

It all started when I began tutoring a woman who wanted to master English and move to the U.S. Before long we became more than tutor and student. Soon we were romantic and barreling toward matrimony. I felt unbelievable pressure. It was scandalous for her to have a boyfriend and no plans of marriage. Even more scandalous to be dating an American.

She was beautiful. Bright and funny. And I let myself get caught up in all of it. Thought that a deeper love and understanding would come later. As if it were something we could manufacture and cultivate ourselves.

We married way too soon. Before we’d had time to learn crucial things about each other. Before ever truly knowing each other. She knew I wanted to move to the U.S. though. As soon as possible. It’s one of the first things I told her. But neither of us thought it would happen so fast. That within that first year I’d find a job like the one in Pueblo. And ultimately, like a lot of Lebanese, she’d realize she didn’t really want to leave friends and family. Or her home. No matter how dangerous that home was.

When I got my job in Colorado she came with me. At first. But she hated Pueblo. Felt bored with Colorado. So she went back to Lebanon. My first year in Colorado, and for most of our short marriage, we lived on opposite sides of the Earth. During that entire year we maybe spent a total of three or four weeks under the same roof. I was miserable when I visited her in Beirut. Especially without my job at AUB. And she was miserable whenever she was in the U.S. with me. One of us always homesick and too reliant on the other. No balance at all. And no similar interests. We hadn’t had the time to figure it all out beforehand.

We’d hit a wall in the dark. Stumbling around blind, neither of us able to climb or figure a way around.

Divorce is incredibly sad. Even in the best of situations. Even when there are no children or assets to fight over. Especially for her. A divorced woman in the Middle East? It’s terrible. And not a day goes by that it doesn’t haunt me.

Antoine Chahine, the head of Housing at AUB, only housed people like me in places where he got kickbacks. Francophone had been a convenient excuse to convince me and my colleagues that the Orient Queen was the only possible place to live. And I ended up hating it there, but when I told them I was moving out early, they delivered me a bill for all the “extra” charges they’d never told me about. Charges that, had I known of them the first month, I would’ve paid and left immediately. Instead they’d been secretly accruing for almost a year.

And I couldn’t pay.

Although I probably should’ve found a way. But it was more the principle of the situation so I fought them on it. Like a fool. Little did I know my landlords were part of Amal, one of the most powerful terrorist groups in Lebanon. And they contacted the authorities. Placed my name on a list at the airport so I couldn’t leave the country and came looking for me. For days I hid out, living as a fugitive until Najib, an attorney friend of mine, helped broker a deal for my safety.

Still, I didn’t pay. I couldn’t. And still they threatened to collect in any way they could.

Finally, Jim Radulski, the head of Human Resources at AUB, called me in for a meeting. He and everyone else at the university had expected me to pay after enough harassment, a night in jail maybe. Or worse. But when that didn’t happen my employers were forced to deal with it, so that no harm came to me to make the university look bad. So Radulski bartered his own deal where AUB paid the cost of what I’d been extorted for and set up a plan for me to pay half of it back. But first I made him get my name off the airport list so I could leave the Middle East. And later, when he finally did, I’ve never felt so light or free as when that plane lifted off the runway, off Lebanese soil, and carried me home.

Where I am lucky to be alive.

Lucky for the amazing job I have and the incredible students I work with in Pueblo. In a way I wish they’d never graduate so I could continue working with them indefinitely. But I want them to graduate. To succeed. And go on to be as happy in life as I am. No. Happier.

I’m fortunate to be where I am, I know. Grateful to be intact after all the mistakes I’ve made. The regrets. The sleepless nights. Staring up through blackness for hours on end. The wild years. The darkness. I’m lucky I’ve survived long enough to reign it in. To start the difficult, but essential work, of taming the tendency toward chaos.

Still, I am haunted by the battles I’ve fought.

And haunted by all these ghosts.